As the world continues to grapple with the ramifications of industrialization, a provocative question emerges: Is climate change overestimated or underestimated by science? This query not only sparks academic debate, but it also invites a thorough exploration of the scientific methodologies, societal implications, and political responses that shape our understanding of this global crisis. Throughout this discourse, we will examine varied perspectives and data interpretations, ultimately revealing the complexities ensconced within climate science.

To embark upon this intellectual journey, one must first delineate the foundational premises underpinning climate science. The prevailing consensus among climate scientists asserts that human activities—especially the combustion of fossil fuels—are the primary drivers of climate change. Nevertheless, the multiplicity of climate models and projections casts a shadow of uncertainty. Algorithms designed to predict future conditions rely on a plethora of variables, including carbon emissions scenarios, societal adaptation strategies, and even technological advancements. Consequently, the potential for both overestimation and underestimation lurks within these models.

Consider the phenomenon of overestimation. Critics often argue that the alarmism surrounding climate change is excessively dramatic. The dramatic rise in the frequency and severity of natural disasters has led some to extrapolate dire scenarios, portraying a dystopian future characterized by cataclysmic floods, relentless droughts, and widespread biodiversity loss. Nevertheless, this alarmist rhetoric can inadvertently engender skepticism, particularly among those who perceive these projections as hyperbolic. The media’s portrayal of climate-related events can sometimes exacerbate this effect, sensationalizing data without scientific context. In this light, is there a risk that climate change is exaggerated for the sake of raising awareness?

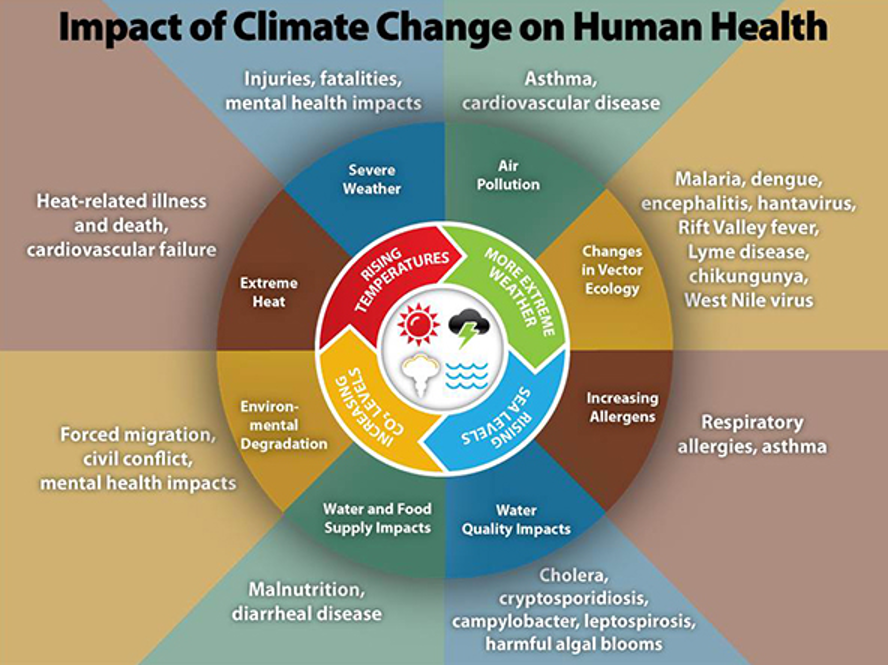

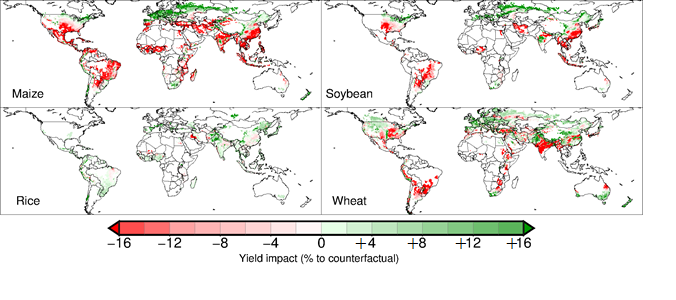

On the other hand, the possibility of underestimation looms large in academic discourse. According to various scholars, existing climate models may inadequately account for certain critical factors, including feedback loops and tipping points in Earth’s climate systems. For instance, the melting of polar ice caps contributes to rising sea levels, prompting further ice melt, which can create a vicious cycle of warming. Additionally, the complexities of oceanic and atmospheric interactions remain poorly understood, leaving concerning gaps in current projections. Therefore, could it be that the impending consequences of climate change manifest with far greater severity than the scientific community is currently prepared to acknowledge?

To further dissect this dichotomy, one must explore the socio-political implications of how climate change is reported and discussed. The intersection of science, policy, and public perception engenders a multifaceted battleground. On one side, climate activists and researchers advocate for aggressive policy measures to curb emissions, premised on the urgency conveyed by predictions of catastrophic outcomes. Yet, the counterarguments arise from economic considerations and the notion of feasibility. Critics posit that the societal upheaval necessitated by radical environmental reforms could lead to economic destabilization. In this regard, do the perceived benefits of immediate action outweigh the potential risks, or conversely, are we inadequately preparing for an inevitable crisis?

Moreover, let us consider the psychological dimensions entwined in this debate. The human propensity for cognitive dissonance plays a crucial role in shaping public attitudes towards climate change. The overwhelming nature of dire predictions elicits fear, which can lead to either apathy or denial as individuals grapple with the implications of action versus inaction. As a result, an essential inquiry presents itself: how can the scientific community effectively communicate the urgency of climate change while avoiding sensationalism that could alienate the public? Communication strategies must be refined to elicit informed discourse rather than fear-based reactions.

As scientific understanding evolves, so too does the nature of climate advocacy. Recent discussions have emphasized the importance of framing climate change within a context of opportunity rather than solely as a prelude to disaster. Innovative technological advancements, such as renewable energy sources and carbon capture methods, suggest that proactive adaptation could transform the narrative from one of helplessness to one of empowerment. Therefore, could this shift in perspective provide a means to reconcile the perceived overestimation and underestimation of climate change?

In contemplating the prospects for the future, it is essential to recognize the inherent uncertainty that accompanies climate science. The dialogue surrounding climate change must embrace a nuanced perspective that acknowledges both the risks of overestimating the threats and the dangers of underestimating the urgency. This balancing act requires relentless vigilance and thoughtful engagement with emerging data. In doing so, communities can foster resilience and adaptability, ultimately championing a harmonious relationship with our planet.

As we navigate the labyrinthine landscape of climate science, the question of whether climate change is overestimated or underestimated is not merely an academic exercise but rather a potent inquiry that demands our collective attention. The future of our planet hangs in the balance, urging us to confront uncomfortable truths while pursuing innovative solutions. Only through a comprehensive understanding and proactive engagement can we hope to forge a sustainable future for generations to come.

Leave a Comment