When one embarks on a traverse up a glacier, a curious phenomenon emerges: as you ascend, the ice underfoot seems to age before your very eyes. This apparent aging is not merely a superficial observation; rather, it hints at intricate processes that govern the life cycle of glaciers and the frozen landscapes that inspire both awe and contemplation.

To understand how ice gets older as you walk up a glacier, we must first appreciate the formation of glacial ice itself. Glaciers are not simply vast bodies of ice; they are dynamic systems comprising layers upon layers of compressed snow. This metamorphosis begins with fresh snowfall, which, over time, settles and becomes compacted under the weight of successive layers. The initial fluffy snowflakes transform into firn—an intermediate stage characterized by granular ice. Eventually, as the firn undergoes further compression and re-crystallization, it loses air pockets and transitions to glacial ice, a dense and solid material.

This transformation is time-consuming. The deeper you venture into a glacier, the older the ice becomes. Thus, an ascent along the glacial slope equates to a temporal journey back through the history of the glacier. Younger ice is lighter, often tinged with blue hues, as air bubbles trapped within reflect light differently than older ice. This visual distinction becomes apparent to any observer with keen eyes; it is a physical manifestation of time’s passage.

As one approaches the terminus of the glacier, the ice appears not only younger but also more malleable—indicating the high energy of the system. Here, the ice is continually fed by fresh snow, giving it a lively, vibrant character. Contrastingly, the ice further up the slope becomes a firmer, ancient relic. The deformations and stratifications tell a story spanning decades, centuries, or even millennia. This stratification—where compressed layers can be counted like the rings of a tree—reveals historical climate data and patterns that can inform scientists about past environmental conditions.

The compression process that generates glacial ice entails a gradual loss of air. In pristine, freshly fallen snow, the air content may approach 90%. As a snow layer undergoes compression, it transforms, losing air until the density increases substantially. This results not only in a coalescence of the snow crystals but also in a skeletal framework where gas bubbles are encapsulated in the longer, more solid crystalline structures of mature glacial ice. The deeper you move into the glacier, the more these air pockets become scarce, giving the ice a distinct character and antiquity.

The older ice found higher up the glacier possesses unique properties that intrigue glaciologists and environmentalists alike. Among these is the notion of inclusions. Minute particles and traces of atmospheric gases trapped during the formation of the ice are preserved within. These serve as archives of Earth’s atmosphere and climate, providing invaluable data for researchers studying climate change and historical weather patterns.

Moreover, the intricacies of ice aging go beyond mere physical structure. The glaciers themselves are susceptible to the celestial rhythms of our planet. Fluctuations in temperature and precipitation directly affect the glacier’s mass balance—the equilibrium between accumulation and ablation. This delicate ballet is chronicled in the layers of ice, with variations in thickness, density, and even chemical composition revealing clues about climatic events that have influenced their formation and growth.

In the highest echelons of the glacier, one may find ice that has endured tantalizing epochs of Earth’s natural history, encapsulating not just frost but the whispers of ancient environments. Each layer of ice we tread upon is a commendation of natural processes operating beyond human comprehension. The compelling rift between youth and age in glacial ice vividly illustrates the transient nature of ecosystems and serves as a poignant reminder of our planet’s climatic chronicles.

Each step taken on the slow ascendancy of a glacier is a testament to time’s relentless march. The air grows colder, the glacial ice becomes more resilient, and one is enveloped in an atmosphere that feels imbued with the echoes of ages past. As one contemplates the juxtaposition of transient human existence against the enduring permanence of ice, it becomes clear that there is more to glaciers than meets the eye.

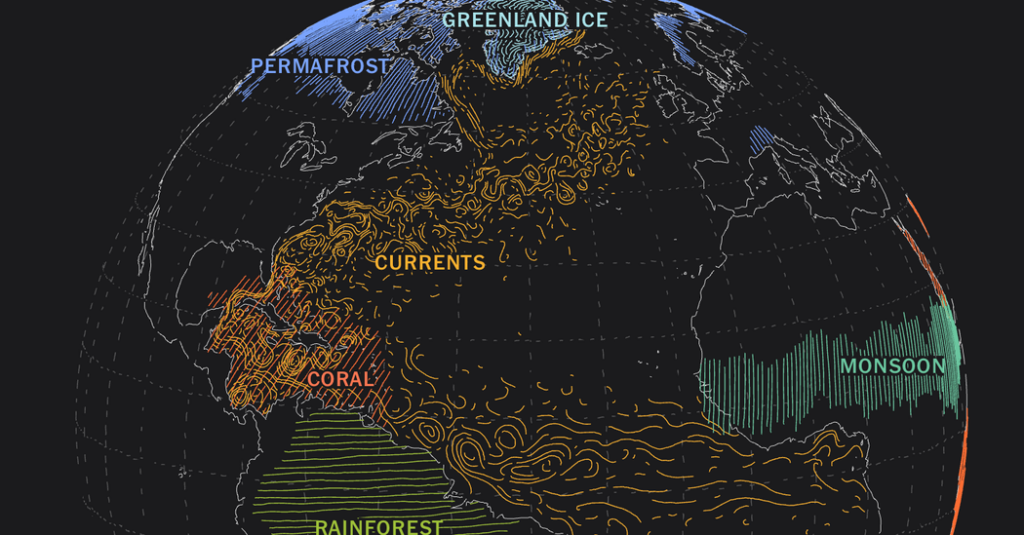

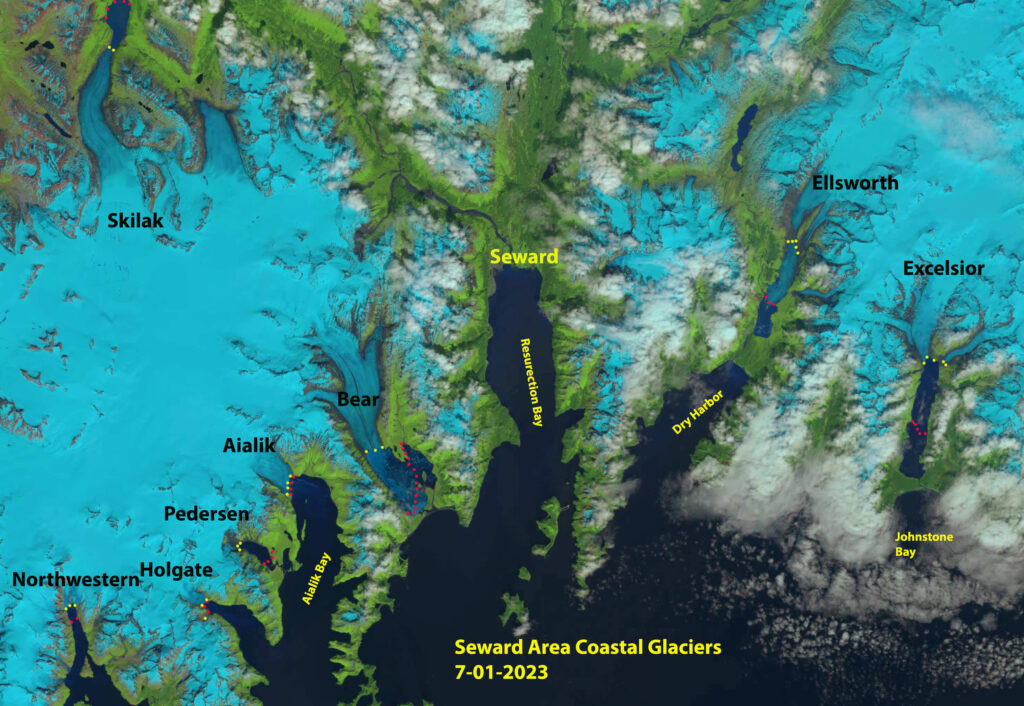

The fascination with this phenomenon lies not only in the natural splendor of glaciers but also in their underlying importance as indicators of climate change. As global temperatures rise and glaciers retreat, the ancient ice that reveals our planet’s history is slowly vanishing. The ice we encounter today might be among the last remnants of past climates, emphasizing the urgency with which we should address environmental stewardship.

Ultimately, the maternal embrace of a glacier invites deeper reflection, urging observers to engage with the delicate balance of nature. Each hike up the ancient ice serves as a reminder of the roles we play in this exquisite ecological tapestry. To walk up a glacier is to traverse not only physical elevation but also the strata of time, environmental cycles, and the legacies of our actions. With each step, the aged ice beneath speaks volumes about our planet—its fragility and resilience, impermanence, and the pressing need for conservation.

Leave a Comment