The modern world, with its relentless advancements, is akin to a double-edged sword. On one hand, it offers unprecedented comfort, while on the other, it wreaks havoc on our environment. Air conditioning epitomizes this contradiction. As the temperature of our planet escalates, many turn to this technology for respite. However, the question arises: Does air conditioning make climate change worse? This inquiry unveils a complex interplay of comfort, consumption, and consequence.

To navigate the intricacies of air conditioning, one must first understand its fundamental operation. Air conditioners work by transferring heat from inside a building to the outside, utilizing refrigerants to cool the air. This process, while effective, is not without its environmental toll. Refrigerants, particularly hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), are potent greenhouse gases. Their global warming potential dramatically exceeds that of carbon dioxide, often by thousands of times. Therefore, as the demand for air conditioning proliferates, so too does the emission of these harmful gases.

Consider the metaphor of a double-helix—representing both comfort and environmental impact. One strand symbolizes the relief air conditioning provides from scorching heat, while the other represents its contribution to climatic disruption. The spiraling coils of this helix remind us that these two aspects are inextricably entwined. As we heat our homes, we may inadvertently stoke the flames of global warming.

Moreover, air conditioning systems consume considerable energy. In the United States alone, they account for nearly 12% of all residential electricity usage. As the demand for electric cooling continues to rise, primarily due to climate change-induced heatwaves, the burden on our power grids intensifies. Many regions rely on fossil fuel-based electricity, further exacerbating carbon emissions. Thus, the very act of seeking personal comfort through air conditioning becomes a paradox, throttling our efforts to combat climate change. Every chilled room adds to the atmospheric burden, revealing a painful irony: we cool ourselves while simultaneously heating the planet.

The impacts of air conditioning are not confined to energy consumption alone. The urban heat island effect illustrates another layer of complexity. Cities, with their extensive concrete and asphalt surfaces, absorb and retain heat. Air conditioners, in attempts to counteract this localized warming, release more heat into the environment. This practice forms a vicious cycle; as urban areas grow hotter, more energy is consumed for cooling, thus raising temperatures further. It is a troubling feedback loop, where infrastructure designed for comfort becomes a catalyst for increased climate adversity.

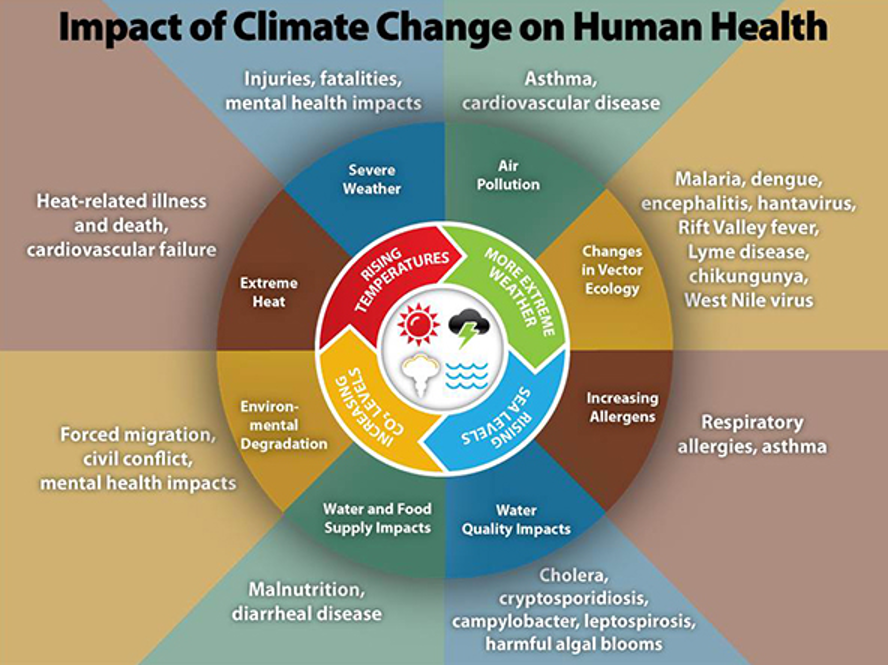

Looking beyond the immediate ramifications, there are broader societal implications to consider. As temperatures rise globally, the dependency on air conditioning escalates, creating a digital divide. Regions with limited access to cooling technology experience higher mortality rates during heatwaves. This disparity in resources not only highlights a pressing social justice issue but also fosters an environment where the privilege of comfort expands at the expense of those less fortunate. Climate change, thus, is not merely an environmental challenge; it manifests in a tapestry of inequalities that air conditioning exacerbates.

Nonetheless, the narrative does possess a flicker of hope. Innovations in air conditioning technology hold promise for mitigating its detrimental effects. The emergence of energy-efficient systems aims to reduce electricity consumption while maintaining comfort. Furthermore, the development of low-global warming potential refrigerants seeks to wean us off HFCs. These strategies may transform air conditioning from a formidable foe into a potential ally in climate action.

Passive cooling techniques provide another avenue for reducing dependence on conventional air conditioning. Architectural designs that emphasize natural ventilation, shading, and green roofs can significantly decrease indoor temperatures without the need for mechanical cooling. The revival of traditional cooling methods, along with an embrace of modern energy-efficient technologies, could forge a path towards a balanced coexistence with our environment.

The conversation surrounding air conditioning and climate change also necessitates a reassessment of our cultural relationship with comfort. Society often equates comfort with privilege and ease, forgetting the environmental ramifications. A shift towards embracing moderate temperatures and exploring alternatives to mechanical cooling would not only ease the strain on our climate but also promote a more sustainable mindset. We must redefine comfort, finding solace in diverse, eco-friendly practices that honor our planet.

As we stand on the precipice of climate catastrophe, the righteous urgency for introspection looms large. Air conditioning serves as a symbol of our greater struggle against climate change—its dual nature reflecting our complexities as a species. It is a stark reminder that comfort and conservation must walk hand in hand if we are to forge a sustainable future. While air conditioning offers solace in sweltering times, we must confront its implications, striving toward solutions that cool our surroundings without inflating our carbon footprints.

In sum, the question of whether air conditioning makes climate change worse is not merely a query of mechanics; it is a conundrum steeped in ethics, responsibilities, and the pursuit of balance. As the earth continues to warm, the urgency for nuanced conversations and innovative solutions becomes paramount. We can no longer afford the luxury of ignorance; it is essential we confront the paradox of comfort and reimagine a future where our pursuit of relief does not jeopardize the very planet that sustains us.

Leave a Comment