The intricacies of nutrient cycling in terrestrial ecosystems represent one of nature’s most profound symphonies. Nutrients, those elemental building blocks of life, circulate endlessly, enabling terrestrial biomes to flourish. Understanding this process is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for appreciating the delicate equilibrium upon which our environment relies.

At its core, nutrient cycling refers to the movement and transformation of essential elements through various biotic and abiotic components of an ecosystem. Primary among these nutrients are carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur—elements critical for the survival and growth of organisms. Each cycle intricately interlinks, demonstrating the dynamic interdependence within terrestrial ecosystems.

The carbon cycle is often the cornerstone of nutrient cycling discussions. It begins with the process of photosynthesis, where green plants and phytoplankton utilize sunlight to convert carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into organic matter. Through this fundamental process, carbon is sequestered in biomass, providing a basis for life. Yet, the carbon cycle does not end with plant growth. When organisms die or excrete waste, organic carbon returns to the soil, where it can be decomposed by microorganisms. This microbial decomposition is vital; it breaks down complex organic molecules, releasing nutrients back into the soil in forms that can be re-assimilated by plants.

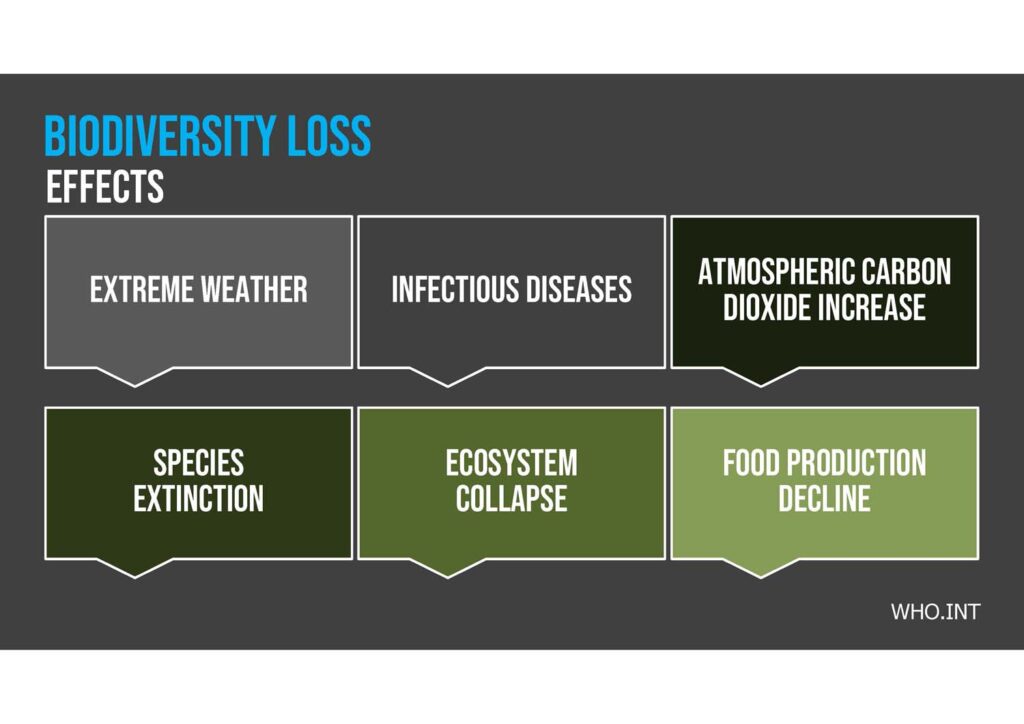

As one reflects on the implications of the carbon cycle, consider its unmistakable impact on global climate. The balance between carbon sequestration in forests and its release through respiration and combustion plays a pivotal role in climate regulation. Disruption of this cycle, through deforestation or fossil fuel combustion, exacerbates atmospheric carbon levels, contributing to climate change and its widespread repercussions on biodiversity and human societies.

Next emerges the nitrogen cycle, which, while less visible, is no less critical. Atmospheric nitrogen, constituting about 78% of the Earth’s atmosphere, is largely inert and cannot be used directly by most living organisms. However, nitrogen-fixing bacteria, found in the root nodules of legumes and in the soil, convert this atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, a process profoundly important for the biosphere. The ammonia can then transform into nitrites and nitrates, forms that plants can absorb and utilize for growth.

Yet, the narrative of the nitrogen cycle becomes more complex as one considers the phenomenon of eutrophication, often spurred by excessive nitrogen runoff from agricultural practices. Such nutrient pollution can lead to algal blooms in aquatic ecosystems, creating dead zones devoid of oxygen, which in turn devastates marine life. Thus, the interplay of the nitrogen cycle with agricultural practices necessitates a reevaluation of our interactions with the land.

The phosphorus cycle breaks this cyclical mold. Unlike carbon and nitrogen, phosphorus does not have a gaseous phase; instead, it cycles through rocks, soil, water, and organisms. Initially, phosphorus exists primarily in mineral forms, gradually weathering into soluble forms that can be taken up by plants. A significant aspect of the phosphorus cycle is its slow movement, a characteristic that can lead to the depletion of this essential nutrient in agricultural soils if not replenished through organic or inorganic fertilizers. Additionally, an excessive use of fertilizers carries the risk of phosphorus runoff, similarly leading to eutrophication and aquatic ecosystem imbalances.

These elemental cycles do not operate in isolation; they interact in intricate ways, shaping the very essence of terrestrial ecosystems. As one examines these cycles, it becomes evident that they form a web of life. Mycorrhizal fungi, for instance, illustrate interlinked nutrient dynamics. These fungi establish symbiotic relationships with plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake—especially phosphorus—while benefiting from carbohydrates produced by the plants. It is a mutualistic exchange that exemplifies the principles of nutrient cycling, highlighting how interdependence fosters resilience and sustains ecosystems.

Beyond mere nutrient movement, the implications of nutrient cycling resonate through ecological succession. In the early stages of ecosystem development, nutrients are often scarce. However, as organic matter accumulates and decomposition rates increase, richer, more diverse communities emerge. This ecological maturation fosters improved nutrient cycling processes, illustrating how established ecosystems become self-sustaining systems teeming with life.

In contemporary society, the urgency of understanding nutrient cycling is underscored by the pressing challenges of land degradation, habitat loss, and climate change. A shift in perspective is imperative; we must recognize our role not merely as observers but as active participants in these cycles. Sustainable land management practices, such as permaculture and agroecology, emphasize the restoration and enrichment of soil health, underscoring the idea that nurturing the natural processes of nutrient cycling can lead to more resilient agricultural systems.

In conclusion, nutrient cycling represents an intricate dance of nature, a powerful reminder of the interconnectedness of life. As we delve deeper into these cycles, it is essential to acknowledge the responsibilities we bear towards our ecosystems. Every action we take reverberates through the networks of nutrient flows, shaping the future of our planet. To sustain life on Earth, an appreciation of these processes, an understanding of their complexities, and a commitment to nurturing them are paramount. Let us approach our ecological narrative with a reverent curiosity, knowing that in the delicate balance of nutrient cycling lies the key to a sustainable future.

Leave a Comment