When we burn fossil fuels, a complex chemical reaction is set into motion, releasing an impressive amount of energy. But the question remains: where does all the heat go? This inquiry may seem simple at first glance, but it elegantly underscores the intricate balance of our planet’s thermal landscape. Exploring this subject illuminates not only the immediate effects of combustion but also the broader implications for our environment, climate, and even our daily lives.

First, let us establish the nature of fossil fuels. Composed primarily of hydrocarbons, these substances—such as coal, oil, and natural gas—store energy accumulated over millions of years from the remains of ancient flora and fauna. When combusted, a rapid oxidation process occurs, transforming chemical energy into thermal energy, thereby generating heat. This is a pivotal moment in the broader context of energy transfer. It is not merely the combustion itself that is of interest; rather, it is the lifetime journey of that heat once it escapes into the environment.

The immediate output of this combustion is kinetic and thermal energy, contributing to the phenomena we colloquially refer to as “heat.” Upon release, a sizeable portion of this thermal energy is absorbed by the surrounding atmosphere. This phenomenon is a critical component of the Earth’s energy balance. In fact, around 50% of the greenhouse gases emitted by fossil fuel combustion are reabsorbed by land and ocean systems, contributing significantly to various climatic and ecological processes.

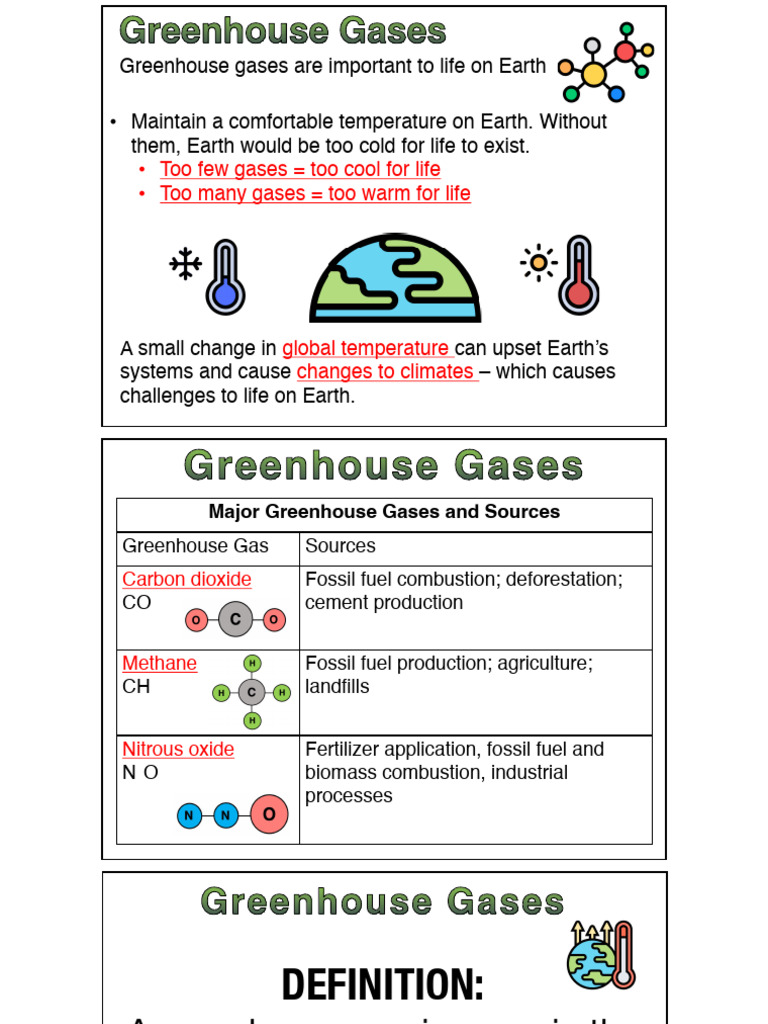

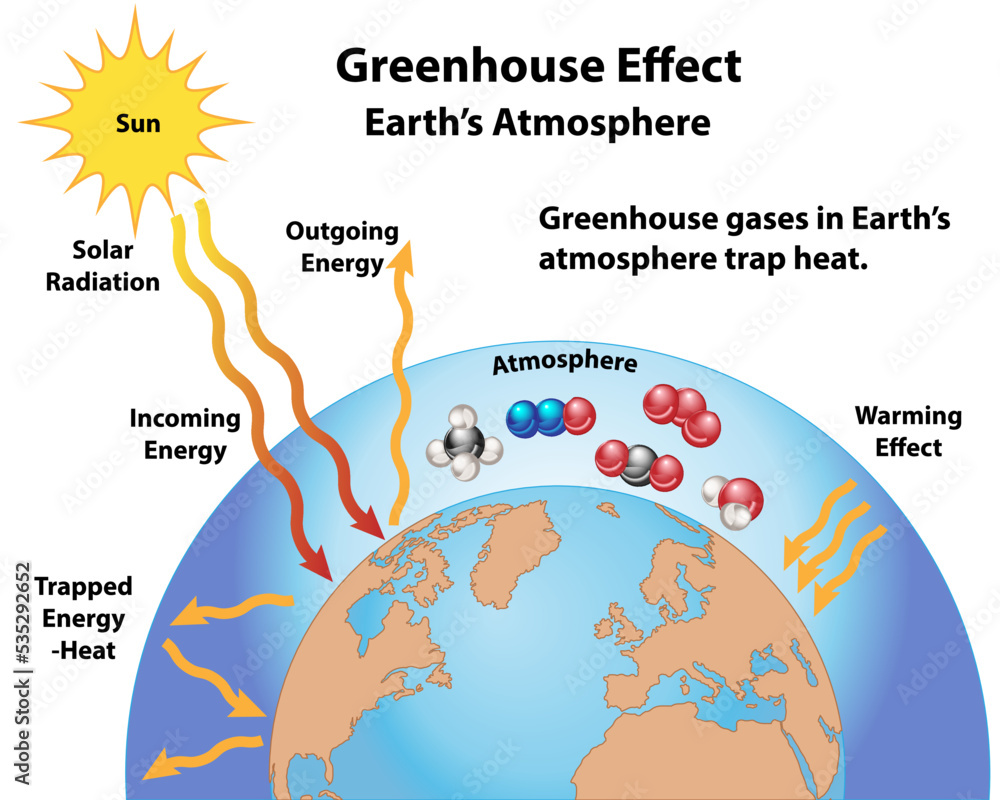

The atmosphere, a seemingly boundless expanse, is composed of various gases that play a crucial role in regulating temperature. As heat is released, it interacts with atmospheric components through a series of complex interactions. Particles and gases absorb the heat but also contribute to re-radiation processes. This concept—longwave radiation—is vital in understanding how much of the heat persists in the atmosphere versus quickly dissipates. Consequently, heat does not merely vanish; rather, it enters a dynamic exchange system, influencing both weather and climate systems with profound consequences.

Additionally, the oceans play a monumental role in the heat’s final destination. With their immense heat capacity, oceans absorb a significant portion of this thermal energy, acting as a global heat sink. As fossil fuels are burned, the oceans level temperature fluctuations, thereby moderating climate extremes. However, this ability to absorb heat comes at a cost. The subsequent rise in sea temperatures contributes to marine ecosystems’ distress, leading to coral bleaching and altered ocean currents, which can have catastrophic ramifications for global weather patterns.

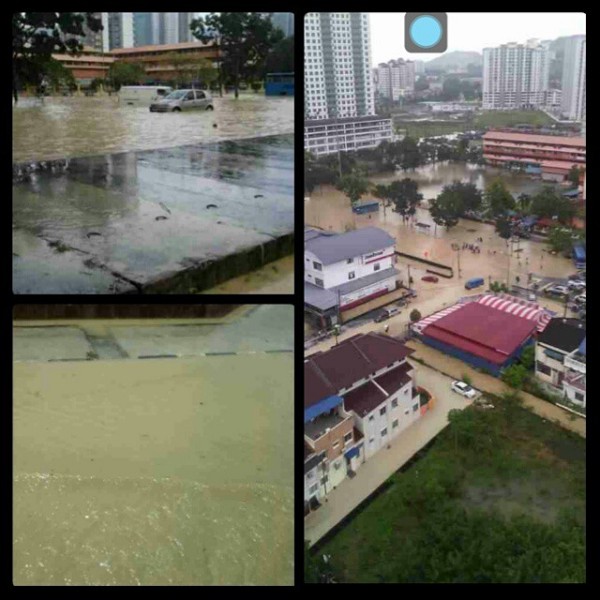

But where it really gets complex is how this heat ultimately interacts with various components of the Earth’s system. As the atmosphere warms, it leads to phenomena such as evaporation, further contributing to weather dynamics. Evaporation of water from the surface of oceans and lakes absorbs heat, thereby cooling the immediate environment but increasing humidity in the atmosphere. This interplay has significant implications for precipitation patterns, which can lead to either droughts or torrential downpours. In this sense, the heat released from burning fossil fuels reverberates through the ecosystem, demonstrating a profoundly interconnected web of cause and effect.

Yet, beyond immediate weather effects lies a monumental adversary—the global climate crisis. The constant introduction of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel consumption is inducing changes on a planetary scale. This external forcing drives long-term climate change, as excess heat contributes to a gradual rise in global temperatures. The somewhat inscrutable nature of this phenomenon lies in its delayed effects—it may take years, if not decades, for the full impact of increased fossil fuel combustion to materialize in observable climatic shifts.

Moreover, anthropogenic heat—heat generated from human activities, particularly from fossil fuel combustion—interacts with natural heat sources and creates feedback loops. For example, as polar ice melts due to rising global temperatures, it reduces the Earth’s albedo effect, which is the reflection of solar radiation. As dark ocean waters or land surfaces replace the bright ice, more heat is absorbed, perpetuating the cycle of warming. Such cascading impacts of heat and climate highlight not just the immediate outcomes of our dependence on fossil fuels, but they underscore systemic vulnerabilities that humanity faces.

A vital area of inquiry remains: how do we reconcile our energy needs with the thermal aftermath of fossil fuel combustion? Transitioning to renewable energy sources could counteract the adverse effects associated with heat generation from fossil fuels. Solar, wind, and hydroelectric power present alternatives that have significantly lower thermal footprints. By embracing renewable energy, we mitigate the heat released into the atmosphere, thereby minimizing our ecological and climatic impact.

In conclusion, the question “where does all the heat go when we burn fossil fuels?” leads us down a path rich with implications. From the atmosphere absorbing thermal energy, to the oceans moderating temperature, and towards the broader context of climate change, the repercussions of fossil fuel combustion extend well beyond mere immediacy. Understanding these dynamics reinforces the necessity for a societal shift in energy consumption and a move towards sustainable practices. The heat may disperse into the environment, but it serves as an ever-present reminder of our energy choices and their long-lasting consequences on our planet.

Leave a Comment