As the world grapples with the inexorable consequences of climate change, the specter of rising sea levels looms ominously on the horizon. Scientists and environmentalists alike have long posited that our planet’s oceans could eventually swell by a meter or more, dramatically altering coastlines and displacing millions. This predicament prompts a pivotal question: how long would it take for sea levels to rise 1 meter globally? To unpack this query, one must delve into myriad scientific, environmental, and socio-political dimensions.

Firstly, understanding the mechanics of sea level rise (SLR) necessitates familiarity with the contributing factors. The two predominant forces driving this phenomenon are thermal expansion and the melting of ice sheets and glaciers. As global temperatures increase due to anthropogenic carbon emissions, ocean water absorbs heat, leading to expansion. Concurrently, the vast ice reserves encapsulated within Greenland and Antarctica are feeling the heat, experiencing accelerated melting rates that contribute to SLR.

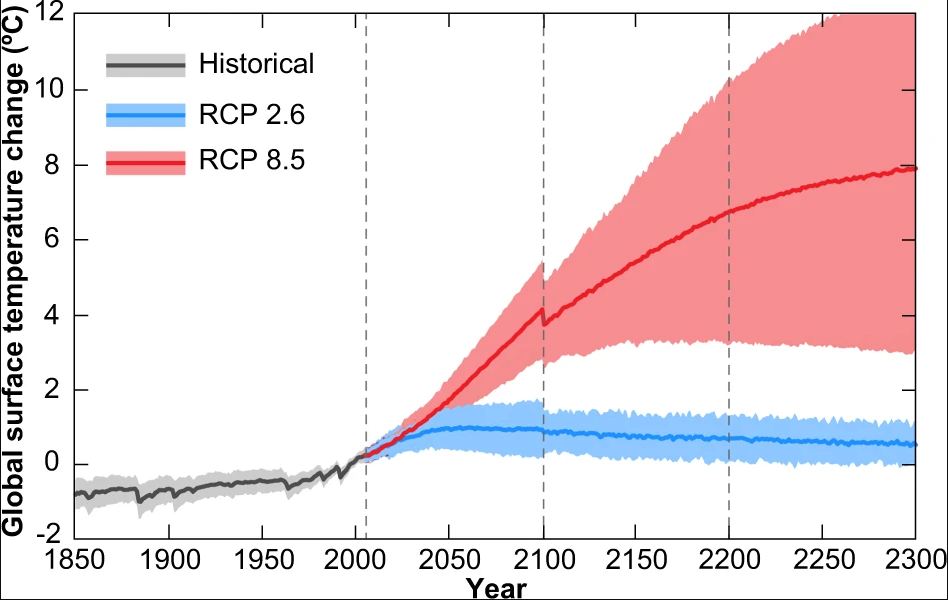

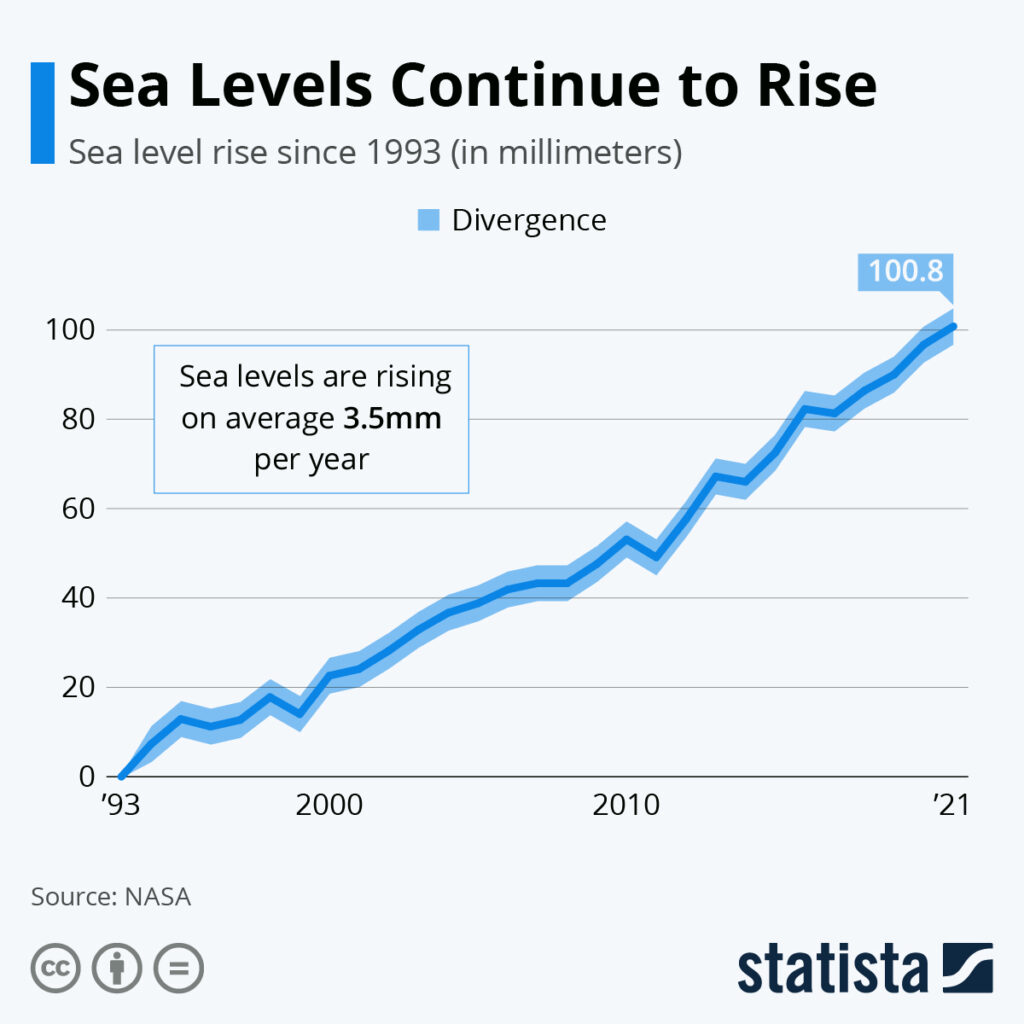

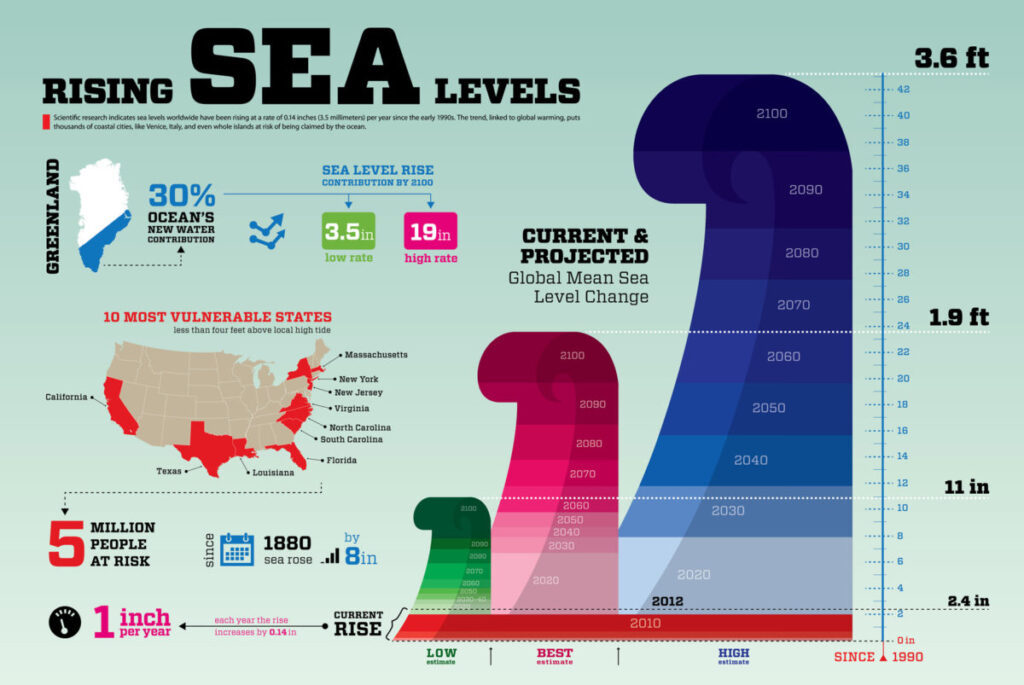

Current projections suggest that the rate of sea level rise is alarming. Historically, seas have risen at an average rate of approximately 1.7 millimeters per year since 1900, but recent data indicates an increase to nearly 3.3 millimeters per year between 1993 and 2020. If this trend were to continue, it could take roughly 300 years to achieve a 1-meter rise. However, this linear approach fails to address the nonlinear dynamics of climate change, where tipping points could trigger far more rapid increases. For instance, if certain threshold temperatures are surpassed, the melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could accelerate SLR drastically.

Beyond the physical science lies the realm of socio-political implications. The overwhelming consensus among climate scientists warns that unless immediate action is taken to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, the trajectory of sea level rise will only intensify. Governmental entities and international coalitions are grappling with the dual challenge of curbing emissions while simultaneously preparing for the inevitable impacts of SLR. Coastal regions, particularly those with dense populations such as New York, Bangkok, and Mumbai, must develop comprehensive adaptation strategies that encompass not only infrastructure resilience but also socio-economic frameworks that support vulnerable populations.

The discourse surrounding climate change adaptation brings us to localize the broader implications of global phenomena. Cities worldwide are attempting to fortify their coastal defenses. For instance, the Netherlands has taken the lead with its intricate system of sea walls and storm surge barriers, designed to withstand increasingly ferocious weather events. Meanwhile, several cities are adopting a more holistic approach, integrating green infrastructure and beach replenishment programs to counteract erosion. These initiatives highlight a shift in perspective, where adaptation becomes as critical as mitigation.

Understanding the economic ramifications of SLR is equally vital. The potential cost of inaction is staggering. According to various estimates, millions of homes, infrastructure systems, and entire cities are at risk. Insured losses from coastal flooding could escalate dramatically as SLR advances, leading to exorbitantly high insurance premiums or, in worst-case scenarios, areas becoming uninsurable altogether. Externalities such as property value depreciation and the potential displacement of communities underscore the urgent necessity of addressing these factors head-on.

Moreover, the geographical nuances across the globe merit careful consideration. Some regions face more acute risks than others. Low-lying areas such as the Maldives and parts of Bangladesh are doubly threatened by both sea level rise and increased storm surges. The interplay of geographic elevation and socio-economic conditions exacerbates the vulnerability of these regions, raising ethical questions about climate justice and the obligations of wealthier nations to assist those who are disproportionately affected.

Furthermore, the intersection of biodiversity and habitat loss cannot go unaddressed. Coastal ecosystems, such as mangroves and coral reefs, serve as natural buffers against storm surges and tidal fluctuations. However, as sea levels crest, these vital ecosystems risk obliteration. The destruction of such habitats not only diminishes biodiversity but also incurs significant environmental and economic costs. Thoughtful policies that incorporate ecological restoration can prove invaluable in safeguarding these ecosystems while concurrently fighting against climate change.

As discussions proliferate regarding sea level rise, one must not underestimate the power of public engagement and education. Communities must be mobilized to understand both the risks they face and the actions they can undertake. Grassroots movements can catalyze passionate advocacy, pushing for sustainable practices and influencing local policy to prioritize climate resilience. A well-informed public can propel governments to act decisively in line with dire predictions and scientific recommendations.

In conclusion, while the timeline remains complex and subject to the vicissitudes of climate dynamics, the potential for a 1-meter rise in global sea levels necessitates immediate attention. From scientific analysis to socio-political action, the multifaceted implications of this looming crisis must be addressed through concerted and sustained efforts. As our planet stands at the precipice of irrevocable change, a unified commitment towards understanding, adaptation, and prevention could dictate the future of countless communities worldwide. Time is of the essence; humanity must choose swiftly and wisely.

Leave a Comment