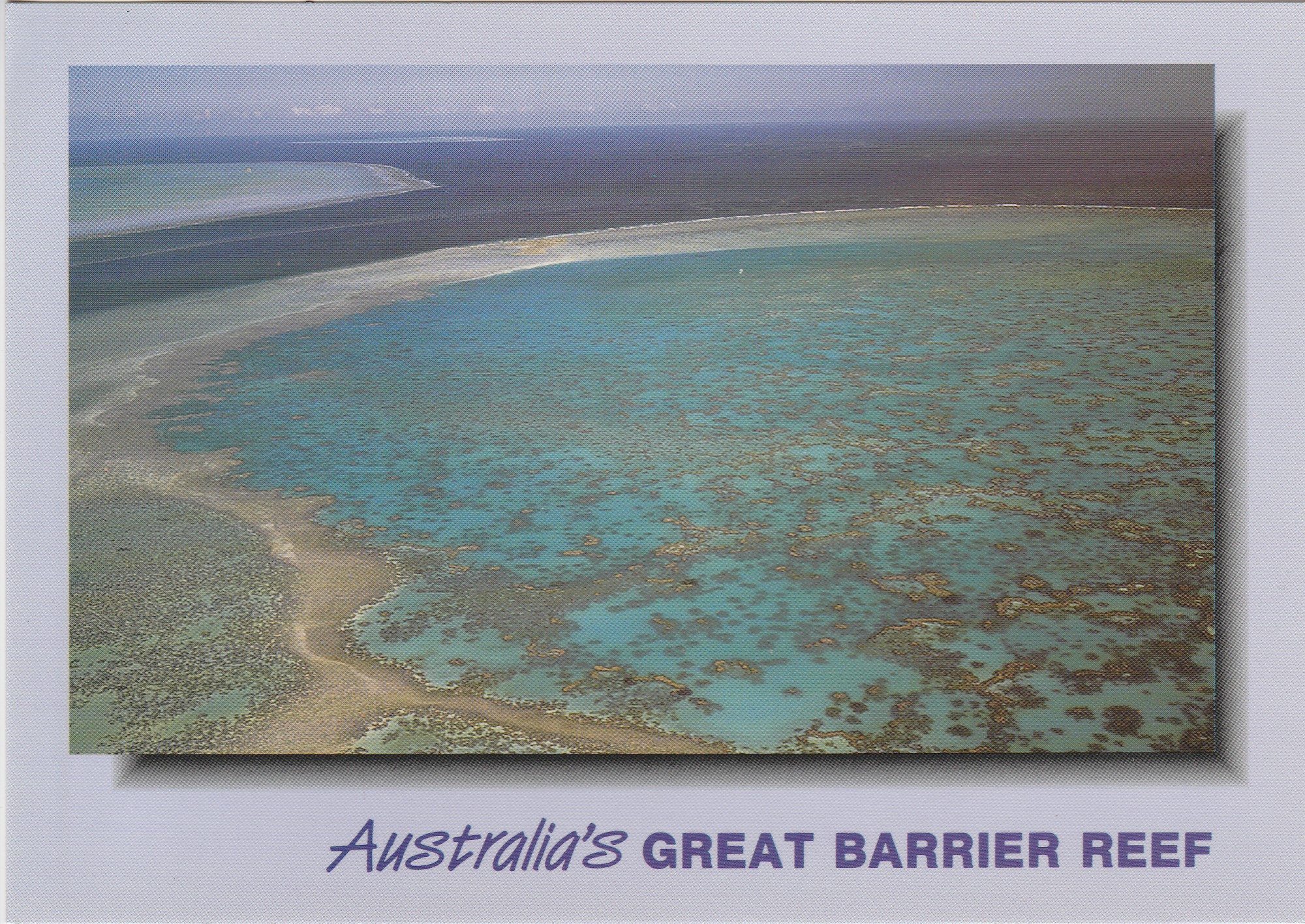

The Great Barrier Reef stands as a dazzling emblem of natural beauty, a veritable Eden of marine diversity that has captivated the hearts and minds of environmentalists, tourists, and scientists alike. Stretching over 2,300 kilometers along the coast of Queensland, Australia, this extraordinary ecosystem is the largest coral reef system in the world. Yet, it has faced grave threats from climate change, pollution, and coastal development. Recently, the Australian government has navigated a diplomatic minefield to forestall a UNESCO downgrade that would label this maritime wonder as “in danger,” a move that speaks volumes about global conservation priorities and national pride.

At the core of the debate lies a perplexing juxtaposition: while the reef is undeniably in peril, the country’s commitment to its preservation has been questioned. Australia’s rejection of UNESCO’s proposition to downgrade the reef’s status can be interpreted not merely as an act of defiance but as a complex interplay of political, economic, and environmental considerations. This insistence on maintaining its World Heritage status reflects a broader attachment to the symbolism of the Great Barrier Reef, which transcends its ecological significance.

The Great Barrier Reef’s allure is palpable, intoxicating even. It harbors approximately 1,500 species of fish, over 400 types of coral, and 5,000 species of mollusks, creating a vibrant tableau that attracts millions of visitors every year. Snorkelers and divers marvel at its kaleidoscopic corals, while researchers delve into its delicate ecosystems, seeking insights into marine biology and climate resilience. Yet, this wonder is overshadowed by its precarious state: rising sea temperatures have caused mass bleaching events, threatening to obliterate much of the reef’s life.

Against this stark backdrop, Australia’s maneuvering becomes even more intriguing. Why the resistance to a downgrade? A prominent observation is that the economic ramifications loom large. As the central pillar of Australia’s ecotourism, the reef generates billions of dollars annually, sustaining thousands of jobs. For many coastal communities, the reef is not merely a resource; it is integral to their identity and livelihood. Acknowledgment of its endangered status could precipitate a loss of tourism revenue, affecting everything from local businesses to national economic standing.

Furthermore, Australia’s geopolitical landscape complicates this issue. As a significant player in the Indo-Pacific region, the nation’s international reputation is entwined with its natural wonders. The Great Barrier Reef does not merely represent marine biodiversity; it embodies Australia’s commitment to environmental stewardship on the world stage. Maintaining a positive narrative around the reef enhances the country’s diplomatic ties and profits, portraying it as an ecological custodian rather than a negligent steward.

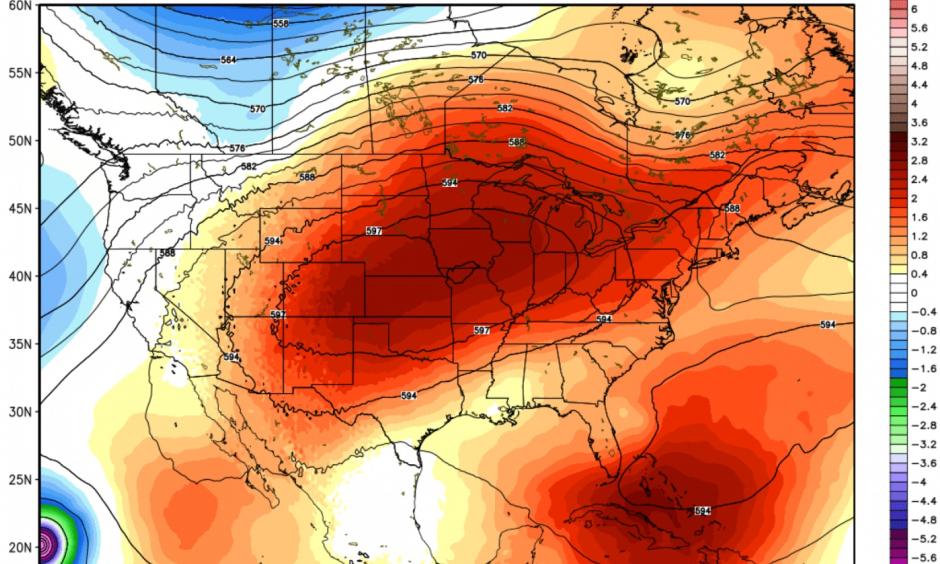

Critically, an examination of the government’s environmental policies unveils a tension between ambition and accountability. Australia has pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, yet the fossil fuel industry, particularly coal mining, remains a substantial economic force. This duality generates skepticism regarding the government’s unwavering defense of the reef’s status. Critics assert that practical action to safeguard its integrity remains insufficient in the face of escalating climate threats.

Moreover, the cultural significance of the Great Barrier Reef cannot be overstated. Indigenous Australian communities have called this region home for millennia, viewing the reef as a living symbol of their heritage and culture. The spiritual connection to the land and sea profoundly influences conservation conversations, highlighting that preservation efforts extend beyond tangible outcomes, encapsulating a holistic view of the natural world. By acknowledging the reef’s fragility, the government must grapple with its implications for Indigenous rights and traditional ecological knowledge.

In the realm of conservation activism, the recent diplomatic tussle embodies a larger existential question for humanity: what value do we place on our planet’s wonders? The Great Barrier Reef serves as a microcosm of the larger fight against climate change, urging individuals and governments to confront uncomfortable truths. As degradation looms, the urgency of the situation escalates. If clipped, this natural marvel could soon become a mere memory, a ghost of its former self—a fate that mankind must fervently work to avoid.

Individual actions also play a crucial role in this narrative. While political machinations dominate the headlines, ordinary citizens possess the power to effect change through informed consumption, advocacy, and community engagement. Each act of protection, no matter how seemingly small, contributes to a collective resistance against ecological decline. Educating oneself about sustainable practices, supporting eco-friendly businesses, and advocating for policies that prioritize environmental health are indispensable steps towards ensuring that future generations will have the opportunity to experience the reef in all its vibrancy.

As Australia embraces its responsibility, the world looks on with both admiration and skepticism. The Great Barrier Reef is more than just a scenic destination; it is a bellwether of our environmental ethics, a challenge that invites both national pride and global scrutiny. In the struggle to balance economic interests and ecological integrity, the nation holds the reins of a monumental narrative—a narrative that will shape the future of this extraordinary ecosystem. Respecting its fragility may just be the key to unlocking a sustainable path forward, fostering a deepened enchantment with the wonders of our natural world.

Leave a Comment