The K–T mass extinction event, now more commonly referred to as the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary, was a cataclysmic occurrence that transpired approximately 66 million years ago. This global phenomenon led to the obliteration of nearly three-quarters of Earth’s species, including a staggering array of fauna that thrived in the lush ecosystems of the late Cretaceous period. One might ponder: What were the dynamics of life on Earth in the ages preceding this monumental extinction, and how did these complex webs of life unravel so dramatically?

The K-Pg boundary, marked by a layer of iridium-rich clay in geological strata, acts as a silent witness to a turbulent history. Among the hypotheses surrounding its cause, the most widely accepted is the impact hypothesis, which posits that a colossal asteroid, roughly 10 kilometers in diameter, collided with Earth near present-day Yucatán Peninsula, creating the Chicxulub crater. The second major conjecture involves extensive volcanic activity, particularly the Deccan Traps in present-day India, which released vast quantities of volcanic gases. This triggered climate upheaval, catastrophic wildfires, and a subsequent “nuclear winter” effect, leading to the collapse of ecosystems. Together, these factors orchestrated a perfect storm of ecological collapse.

Within this context of doom, myriad species fell victim to the devastation. The most iconic casualties were the non-avian dinosaurs, including the majestic Tyrannosaurus rex and the massive Brachiosaurus. Once, these reptiles dominated terrestrial ecosystems—not just as apex predators or colossal herbivores, but also through their role in shaping plant communities. With their extinction, a significant proportion of ecological niches were left barren, giving rise to the question: What might the world have looked like had dinosaurs continued to thrive alongside mammals?

The reptiles known as mosasaurs, formidable marine predators that glided through prehistoric oceans, also succumbed to the extinction event. Their demise was not just a loss for biodiversity but represented the collapse of entire marine food webs. The absence of apex predators like mosasaurs likely contributed to the proliferation of smaller marine reptiles and the eventual rise of new forms of life, altering the trajectory of marine evolution.

While terrestrial reptiles were the tapestry of the Cretaceous landscape, innumerable smaller species also vanished. The flying pterosaurs, which had ruled the skies, were rendered extinct alongside their terrestrial counterparts. Consider the diverse range of ecological roles these animals played; from controlling insect populations to seed dispersal, their absence had cascading effects throughout ecosystems. Can we even begin to fathom the breadth of biodiversity lost when life itself became an endangered phenomenon?

In the shadows of such grand destruction, one must also contemplate the myriad forms of life less voyaged in scientific discourse, but whose loss was equally devastating. The numerous species of amphibians, countless varieties of insects, and an array of less-prominent invertebrates faced oblivion. Yet, understanding these lesser-known casualties allows us to appreciate the complexity of ancient ecosystems. They were vital components, sustaining the very fabric of life. Their extinction sparked a dramatic shift, and the ramifications can still be felt in today’s biodiversity.

As the Earth grappled with the aftermath of the K-Pg event, it ushered in a period of opportunism for many surviving species. Mammals, previously overshadowed by their reptilian neighbors, began to flourish in vacant niches. Small, nocturnal creatures began to evolve, adapting to the demands of a drastically transformed environment. They were the true survivors of this apocalyptic event, leading to the diversified lineages of mammals we witness today.

What if the dinosaurs had not perished? What would the evolutionary trajectory of mammals have looked like over millions of years? Competitors such as the theropods would have continued to dominate and evolve, potentially thwarting the ascendance of mammals to apex positions within ecosystems. The narrative of life on Earth could have diverged significantly, indicating how precarious our evolutionary path is.

Furthermore, examining the repercussions of this extinction necessitates contemplation of the delicate interplay between catastrophe and evolution. While the K-Pg boundary led to immense loss, it also fostered biodiversity rebounds. The species that emerged post-extinction laid the groundwork for the modern ecosystems we interact with today. They demonstrated resilience, adapting to new environmental conditions, and formed complex interdependencies that shape our world.

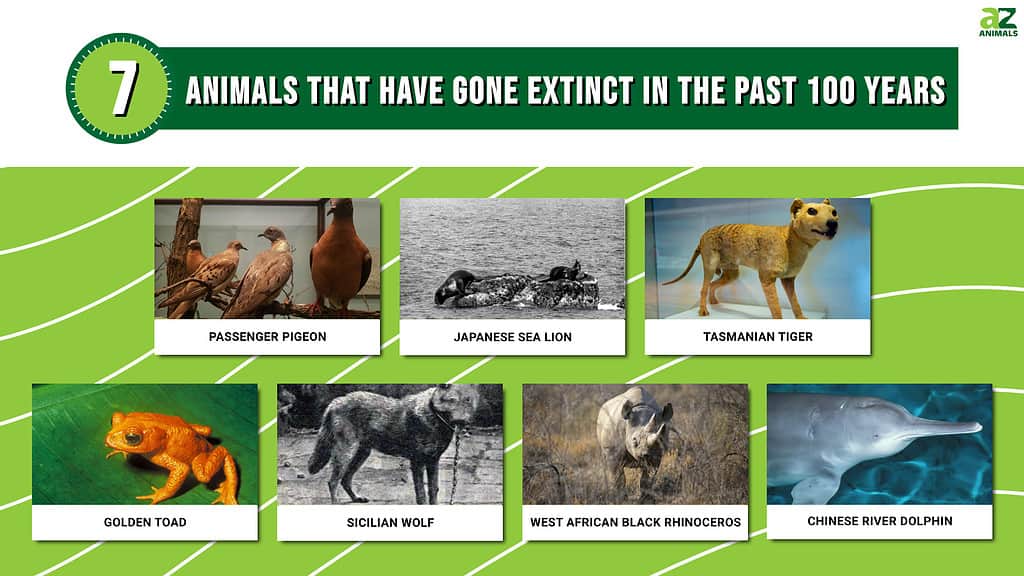

As we reach the conclusion of our exploration of this profound event, one must confront a contemporary parallel: the current biodiversity crisis. The echoes of the K-Pg event serve as both a caution into the unfolding future and an invitation for stewardship. Are we not witnessing a modern-day extinction event fueled by human activities? Consider how the threads of life that once flourished in the reign of dinosaurs can help inform our understanding of today’s environmental challenges. Let us acknowledge that every species holds significance, and we bear the responsibility to protect the remnants and potentials of our planet’s complex tapestry.

Ultimately, the K-T extinction reveals profound truths about resilience, adaptability, and the intricate web of life. As we reflect on this past, we challenge ourselves with a question: What will we learn from history to ensure the survival of our current biodiversity, preventing a repeat of such catastrophic losses?

Leave a Comment