In the intricate tapestry of ecosystems, invasive species frequently find themselves at the center of heated debates. The question of whether an invasive species can cease to be invasive over time is both compelling and multifaceted. In this exploration, we will delve into the complexities of invasiveness, the potential for ecological adaptation, and the shift in perspectives that allows for a reimagining of our relationship with non-native organisms.

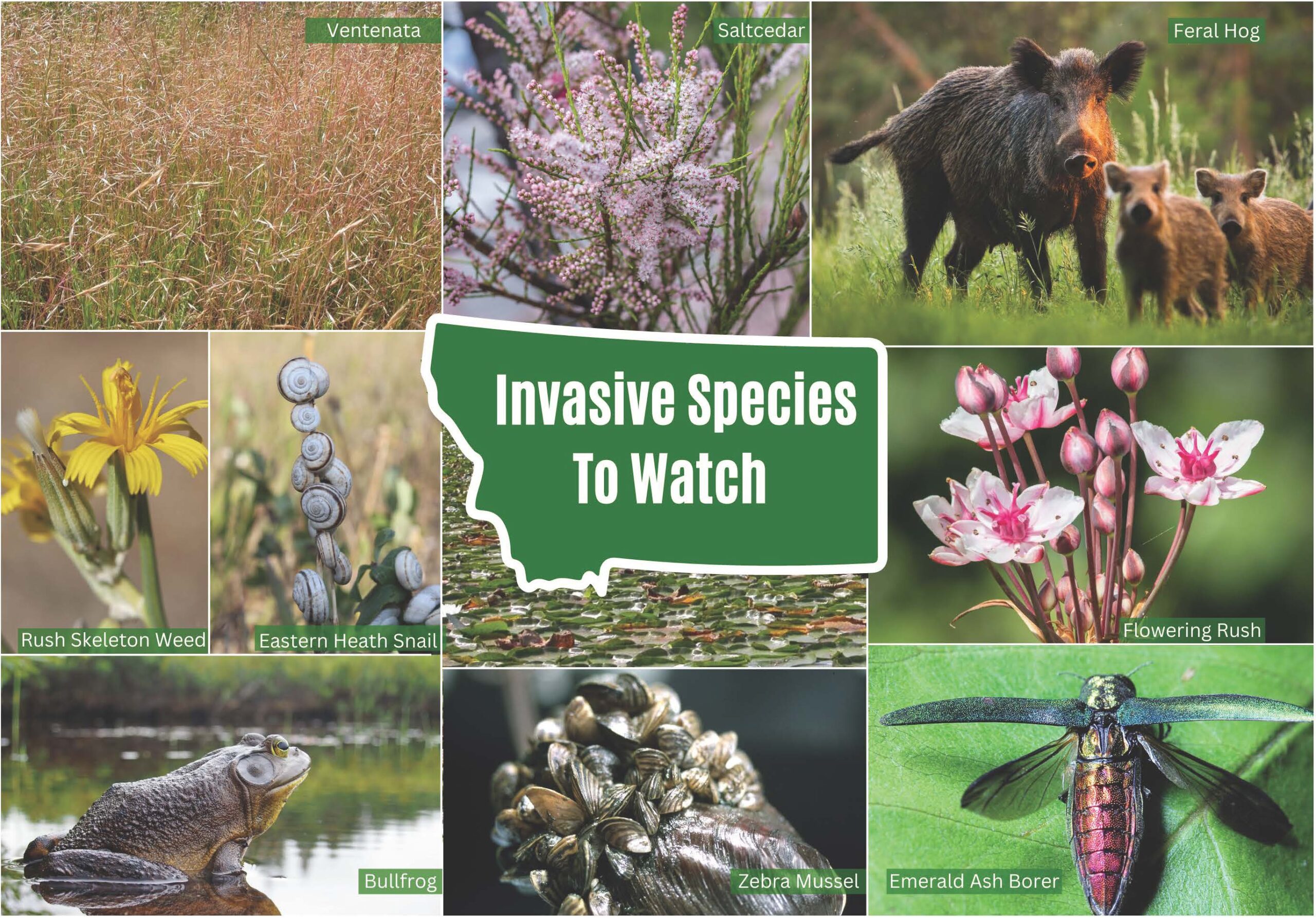

To grapple with the premise of invasive species, one must first comprehend what it means to be invasive. By definition, these species are organisms that are introduced to a new habitat and subsequently flourish at the expense of native flora and fauna. Their rapid proliferation often leads to ecological imbalances, disrupting food webs, and threatening biodiversity. Yet, how does one define the boundary between ‘invasive’ and ‘integrated’ as time progresses?

One of the most significant aspects of the conversation revolves around the concept of ecological adaptation. Invasive species are not static entities. Over time, they may undergo a process of evolution, adapting to the environmental pressures of their new surroundings. This adaptive potential raises intriguing questions. Could an invasive species evolve to play a beneficial role within its adopted ecosystem? Consider the case of the purple loosestrife, an Asian plant notorious for its dominance in wetlands across North America. Though initially viewed solely as a threat, some scientists propose that it may eventually coexist with native species, participating in a broader ecological function as the system equilibrates.

On a related note, the chronological perspective on invasiveness cannot be overstated. The temporally fluid nature of ecosystems implies that the perception of invasiveness may shift with changing environmental contexts. For instance, climate change and urban development are altering landscapes at an unprecedented pace, potentially mitigating or exacerbating the impacts of previously invasive species. Can an environment become more hospitable to an invasive species over time? Or conversely, can a species once categorized as invasive gradually be perceived as an integral component of the ecosystem due to human-induced changes?

Moreover, the question beckons the role of human intervention in this narrative. Management strategies aimed at controlling invasive species often hinge on immediate ecological restoration goals. However, an evolving understanding of species interactions suggests that eradication may not always be the optimal or feasible approach. This calls for a nuanced examination of restoration efforts. For instance, integrating invasive species into restoration plans could lead to unexpected ecological synergies. Could controlled populations of certain invasive species ultimately enhance the resilience of ecosystems in the face of climatic unpredictability or habitat fragmentation?

A paradigmatic shift is necessary for moving beyond the dichotomy of ‘native’ versus ‘invasive’. Ecological relationships are inherently dynamic. Conservationists and ecologists might benefit from adopting a broader lens to evaluate alliances rather than enmity with non-native species. Emphasizing coexistence could prompt a reconfiguration of conservation priorities, redefining what it means for a species to be ‘invasive’. Imagine scenarios where a formerly invasive species is utilized in habitat restoration projects, thereby fostering a new ecological narrative rather than relegating it to the role of villain.

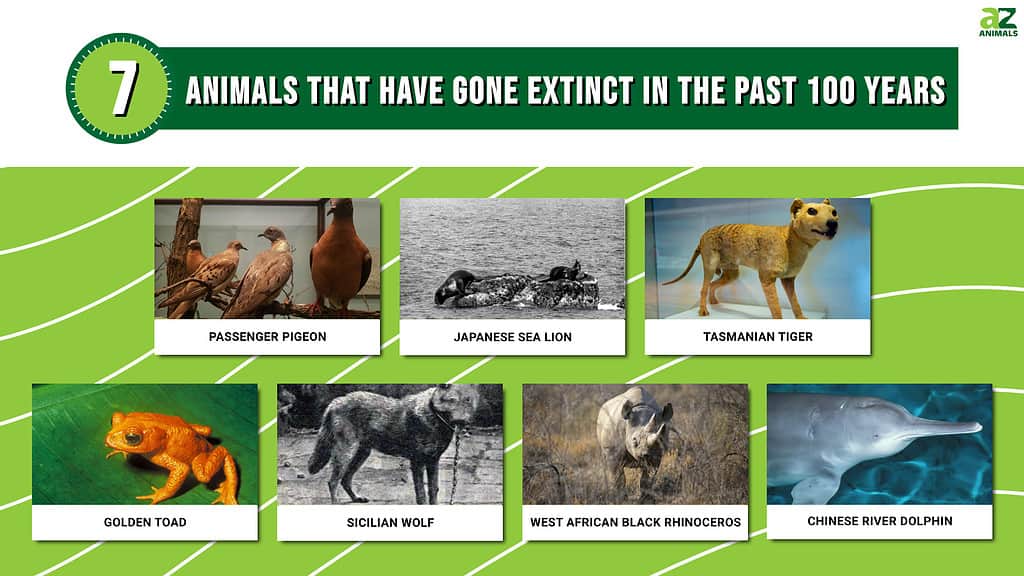

Let us consider the ecological resilience concept, which posits that ecosystems can recover from disturbances, sometimes integrating new species into their viability. This leads us to ponder: can invasive species facilitate recovery in ecosystems that have undergone severe degradation? The resilience of an ecosystem may, paradoxically, depend on the very species initially deemed unwelcome. By examining case studies where invasive species have provided cover for endangered species or restored degraded habitats, one finds evidence of regeneration, challenging preconceived notions of invasiveness.

However, it is essential to approach this reconciliation cautiously. Some invasive species may create irreversible damage, leading to permanent alterations in native community structures. The opposing forces of adaptation and degradation are delicate and situational—each ecosystem tells a unique story influenced by myriad interrelated factors. Therein lies the crux of the inquiry: can we afford to overlook the evolutionary potential for recontextualizing invasiveness based on longitudinal ecological studies?

In conclusion, the journey toward understanding whether an invasive species can cease to be invasive is one of exploration rather than absolutes. The potential for adaptation, the impact of environmental change, and the role of human intervention all conspire to frame this question within a broader narrative of ecological resilience and coexistence. Shifting paradigms, we must cultivate curiosity, fostering an understanding of invasive species that embraces their complexity rather than reducing them to mere threats.

Ultimately, the narrative of invasive species reflects our own human struggle for understanding and harmony with the natural world. By transforming our approach and mindset, we can enrich the ongoing discourse on biodiversity and ecosystem management. The journey towards a more integrated perspective may lead to innovative solutions that not only acknowledge the challenges of invasiveness but also seek to uncover the potential for cooperation within nature’s sprawling web.

Leave a Comment