In recent years, the term “greenhouse gases” has pervaded discussions about climate change, environmental degradation, and sustainability. They have garnered a rather unfavorable reputation, often vilified as the primary culprits behind the planet’s shifting climate patterns. However, a nuanced examination reveals that greenhouse gases (GHGs) possess both beneficial and detrimental aspects. This discourse strives for a balanced analysis of their roles and impacts, urging us to transcend simplistic dichotomies of ‘good’ and ‘bad.’

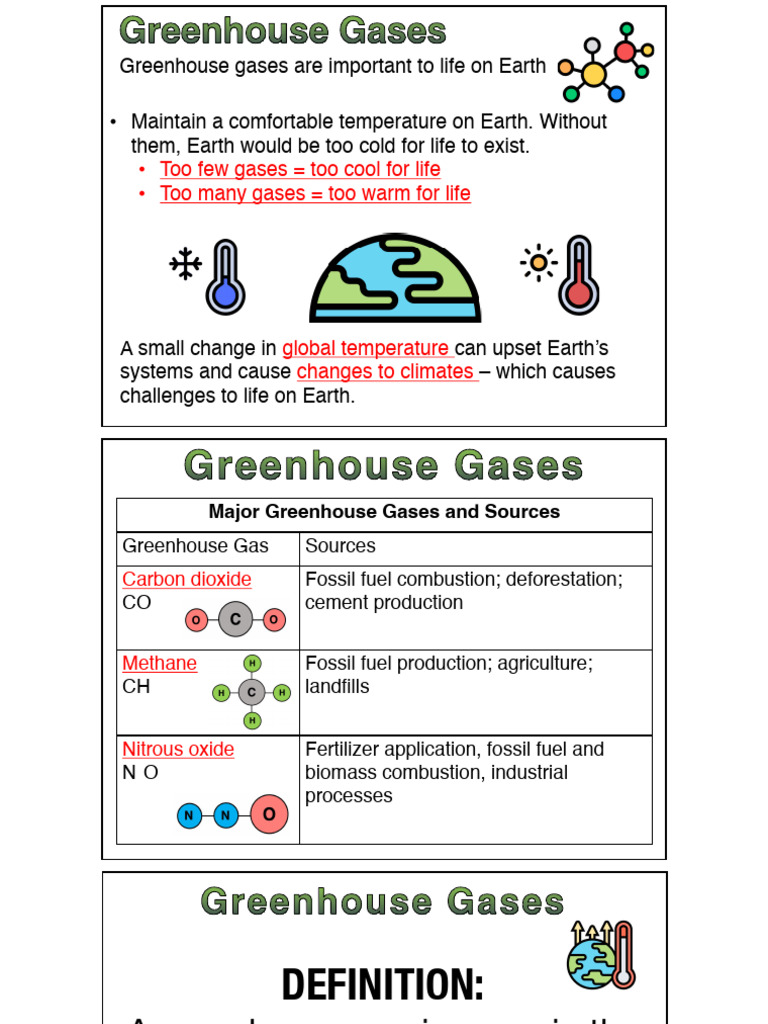

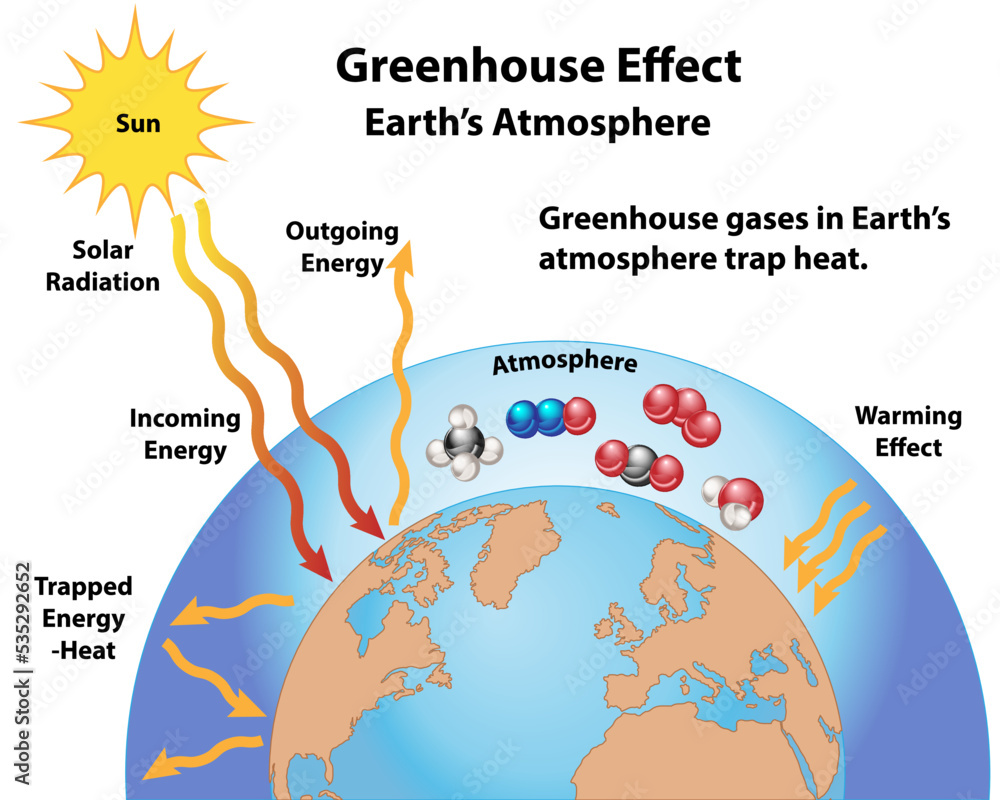

To begin with, it is essential to delineate what greenhouse gases are. The principal culprits include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and fluorinated gases. These gases naturally occur in the atmosphere and play a pivotal role in regulating the Earth’s temperature by trapping heat, a phenomenon aptly referred to as the greenhouse effect. This process is critical for sustaining life on Earth. Without it, our planet would be inhospitably frigid, rendering it inhospitable for the myriad of life forms that flourish today.

One might speculate: how can something initially perceived as detrimental ultimately be beneficial? The answer lies in understanding the delicate balance of GHG concentrations. Throughout history, natural processes have maintained these levels—volcanic eruptions release CO2, while oceans and forests absorb it. Likewise, the decomposition of organic matter produces methane. These natural occurrences contributed to a stable climate conducive to agriculture, biodiversity, and human civilization.

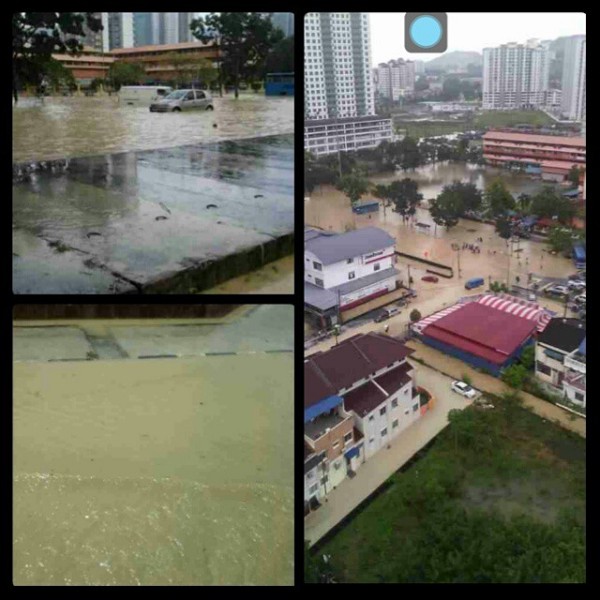

However, the Industrial Revolution marked a significant inflection point. Human activity systematically transformed the landscape of GHG emissions. Fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, and livestock farming escalated the levels of carbon dioxide and methane, surpassing natural regulatory mechanisms. Consequently, the Earth’s temperature began to rise, leading to a plethora of environmental crises—from erratic weather patterns to accelerated glacial melting.

One may argue that GHGs have a dual character—a Janus-faced dichotomy between good and evil, constructive and destructive. On the one hand, these gases are indispensable for maintaining life; without them, Earth would be barren. Conversely, anthropogenic emissions have perpetrated severe climate perturbations that threaten global ecosystems. This paradox evokes the question—are they inherently good or bad?

To address this, one must consider the origins and nature of the greenhouse gases dominating the atmosphere today. Naturally occurring greenhouse gases have a beneficial role, enabling life as we know it. However, when these gases escalate due to human intervention, the outcomes become ominously calamitous. This raises a critical point: it is not the greenhouse gases themselves that are categorically bad, but rather the volumes in which they are released into the atmosphere.

Replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and geothermal can significantly mitigate excess GHG emissions. These energies are often classified as ‘green’ due to their minimal environmental footprint compared to their carbon-intensive predecessors. By transitioning to these alternatives, we can curtail the volume of GHGs and reconcile the balance necessary for a stable climate.

The complexity of this topic is compounded when one considers the role of specific gases. Methane, while far more potent than CO2 in its heat-trapping capabilities—over 25 times more effective within a 100-year timeframe—has a shorter atmospheric lifespan. Thus, while it has a significant immediate impact, reducing methane emissions can yield rapid climate benefits. Conversely, carbon dioxide lingers for centuries, presenting a long-term challenge to climate stabilization. Such differences necessitate tailored approaches to mitigating distinct GHGs.

Moreover, the interplay between greenhouse gases and environmental systems is vital to our understanding of climatic phenomena. Ecosystems such as wetlands and forests act as carbon sinks, absorbing CO2 and thereby positively contributing to the greenhouse gas balance. Conversely, deforestation and land-use changes exacerbate GHG concentrations. Restoration initiatives, such as reforestation and wetland preservation, can foster a synergistic relationship where natural systems help regulate atmospheric GHGs, emphasizing the interconnectedness of climate health and biodiversity.

An overarching ethical consideration also pervades this discourse. Climate justice necessitates a reckoning with the historical contexts of GHG emissions. Industrialized nations, having disproportionately contributed to climate change, bear a moral obligation to aid developing countries in their pursuit of sustainable development. These nations often rely on agriculture and natural resources whose viability is imperiled by climate fluctuations emanating from greenhouse gas emissions. This ethical obligation complicates the discussion of GHGs, calling for a more equitable distribution of responsibility in mitigating their adverse impacts.

In conclusion, the narrative surrounding greenhouse gases is not straightforward. Rather, it embodies a complex tapestry woven from the threads of scientific insight, ecological balance, and ethical considerations. While greenhouse gases indeed possess attributes that enable life, their surfeit, primarily due to anthropogenic activities, heralds a host of environmental challenges. Thus, the objective should not be to wholly vilify GHGs, but to strive for a balanced understanding that recognizes their natural role while taking decisive action to curb their excesses. In embracing this complexity, we equip ourselves with the tools necessary for fostering a sustainable future where humanity coexists harmoniously with the planet’s climate systems.

Leave a Comment